When the Inland Seas staff and volunteers sat down at February’s ISEA Café to discuss microplastics, one thing was immediately clear: we have a plastics problem. Most people in the room had experience on the topic; since 2014 Inland Seas has been taking samples of plastics on the surface of Suttons Bay and Lake Michigan. Most of the samples taken in 2015 are waiting to be analyzed in detail, but a cursory examination of each sample has shown plastic in each and every sample taken. Where does this plastic come from? Who is responsible for preventing it from entering the lakes, and why was it allowed to enter the water in the first place?

Microplastics are particles smaller than 5mm made of plastic; a synthetic material made from a wide range of organic polymers such as polyethylene, PVC, nylon, etc.

In the oceans plastics are also a huge problem, and there are organizations working on solutions. Here, we will talk specifically about microplastics in the Great Lakes.

Where do Microplastics come from?

There are two main sources of microplastics; they come from macroplastics (normal plastic pollution breaking down), and from wastewater discharge that contains tiny plastic particles. Every time someone uses a facial scrub with plastic microbeads, or machine washes a microfleece sweater, microplastics are added to the lakes and streams. Similarly, every mylar balloon, plastic grocery bag, fishing line, or foam cooler that gets away from us near a lake or river breaks down into microplastics if they aren’t recovered.

How much plastic is present in the Great Lakes?

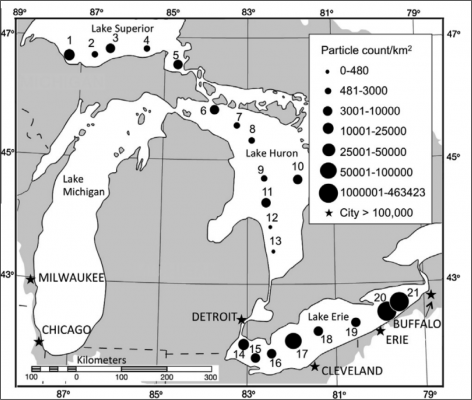

Nobody knows exactly how much is out there, but there have been several surveys that give us an indication of the problem. Below are the results from the first survey of microplastics in the Great Lakes, in 2012. Samples near Buffalo were over 450,000 particles per square kilometer.

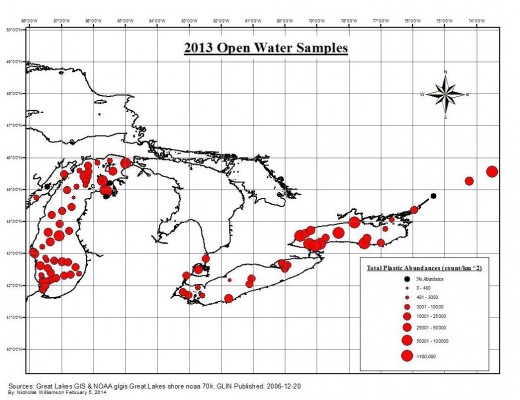

The researchers went out again in 2013 to sample on the other Great Lakes and this is what they found. Each dot is a different sample. Clearly more samples were collected in 2013 than in 2012!

What do microplastics do in the environment?

Microplastics in the environment absorb toxins from their surroundings. Depending on their size and shape, these plastics can appear to be food for plankton or small fish. Due to a process called bioaccumulation, the plastics (and the toxins they absorb) are taken up in the food web and can occur in high concentrations near the top of the food chain. Dissections of fish-eating waterfowl, like the double-breasted cormorant, have shown large concentrations of plastics.

What is being done?

There are lots of groups working on reducing plastics through education, art, and direct lobbying. Research into microplastics is ongoing, but existing research has prompted some legislative action. The President recently signed a bill banning microplastics in wash-off cosmetics, but this does not eliminate microplastics in all consumer products. You should still screen your products for polymers that can escape into the environment. More on how to do that below.

More research will have to be done to understand where concentrations of microplastics are, and the best ways to eliminate their introductions into the environment. You can help researchers by taking samples aboard an Exploring Microplastics Sail.

What should we do?

The bottom line is that we must reduce the amount of plastic we put into the lakes. Once it is released into the environment, there is no way to recapture it again.

Single-use Plastics

Here at Inland Seas, our message is not to eliminate the use of plastics entirely, since plastic is such an useful material. We would like folks to rethink single use plastics like disposable cutlery, cups, food containers, straws, shopping bags, water bottles, etc. Removing these single use products from of our lives could go a long way towards reducing the amount of plastic in landfills and in our environment. Consider the two cups below. Cups A and B are both made with plastic. Does using one over the other make a difference?

Capacity: 300ml

Height: 15 cm

Weight: 44.89g

Capacity: 200ml

Height: 9 cm

Weight: 3.20g

A 2007 study showed that although Cup A is much heavier and took far more plastic and energy to produce, using it just 10 times had the equivalent environmental impact to using a 10-pack of cup B, and discarding each one. What does this mean? Basically, if you can replace any type of single use plastic in your life, even if the replacement is plastic (think swapping flimsy single-use shopping bags for hardy multi-use shopping bags) it only takes a small number of re-uses to decrease your environmental footprint.

Some plastics can be replaced by different materials entirely. Polystyrene, one of the worst environmental offenders, can often be replaced by simple things like popcorn in place of packing peanuts, or fungus in other applications. Many manufacturers are moving back to glass containers which can be almost infinitely recycled and have no negative impact on the environment if they become litter. Others are using more waxed paper and cardboard because of their biodegradable properties.

The Microplastics you buy

There are also many products that contain plastics, already miniaturized and ready to leave your house or business through outflow pipes. These are often items that have exfoliating microbeads or have ‘time release’ properties. Many will be phased out after the Microbead Free Waters Act goes into effect, but some products will not be affected. Read this report by the United Nations Environmental Programme to find out about the extent of plastics in cosmetics. Avoid buying products that contain nylons, copolymers, anything with the prefix poly-

Examples:

- Acrylates copolymer

- Polyethylene

- Polyethane

- Polypropylene

- Polystyrene

- Polyacrylate

- Polyethylene terephthalate

- Polymethyl methacrylate

- Polybutylene terephthalate

- Trimethylsiloxysilicate

We can’t remove the microplastics already in the water, but we can prevent more plastics from entering with work and cooperation between citizens, industry, and government. We have to make the tough decisions to reach for more sustainable options.