By Rachel Ratliff

In 2015, the United States Congress passed H.R. 1321, also known as the “Microbead-Free Waters Act.” This regulation outlines a process for phasing out the production and sale of personal care products containing microbeads, a very small piece of plastic used as an exfoliant. In this post we’re going to define what exactly a microbead is, why it’s harmful, and what you can do to help.

What is a microbead?

Microbeads originated in a Norway University lab. Dr. John Ugelstad made polystyrene (styrofoam) beads of the same spherical size. These small beads were adapted for all kinds of research opportunities including molecular, magnetic, and even industrial research. This versatile tool was free for public use and adaptation.

It wasn’t until the 1990’s that these microbeads started appearing in personal care products like body wash and toothpaste. No longer styrofoam, these beads were made of a harder plastic and advertised as effective exfoliants as shown in this Hayden Panettiere-Neutrogena commercial. Each microbead can range in size from 1 micrometer (1/1000th of a millimeter) to 1 millimeter in diameter. Their densities also vary; some microbeads float in water while others sink to the bottom (Fig 1.).

Why is this a bad thing?

Plastics are a man-made synthetic material. Unlike a banana peel or an apple core, a piece of plastic does not readily decompose, there is no natural process to break plastics down into simple parts to be used again by other organisms. Once a plastic, always a plastic. This means that the plastic water bottle that you saw rolling down the sidewalk today will only break down into smaller and smaller pieces until it’s basically dust, but still plastic. The long-term effects of millions of tiny plastic pieces in the water and soil are yet unknown. With single-use plastic items still part of our everyday convenience culture, the effects will become evident sooner rather than later.

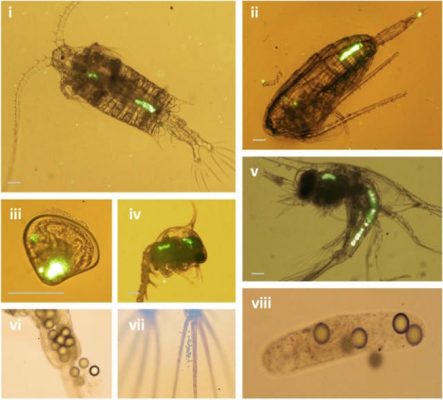

There have been distressing examples, however, of microbeads appearing in the food web. Aquatic animals like fish and insect larvae can be easily duped, and sometimes they mistake the microbeads for a healthy snack [1]. Newsflash: it isn’t. Microplastics contain zero nutritional value. Some pieces are so small that even a plankton can accidentally ingest them (Fig 2). If you ate nothing but nutritionally empty solids for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, you would feel full while your body is literally starving.

The number of plastic pieces per animal only grows as we move up the food web. Imagine an unfortunate plankton who mistook a microbead for food. The plankton then becomes lunch for a small fish. That fish ingests the plankton as well as the small piece of plastic. Does the fish only eat one plankton? Heck no! Do you only eat one potato chip? Let’s say the small fish eats twenty-five plankton and five of them have small plastic pieces in them. That fish has just gone from zero to five pieces of plastic in its belly. BUT WAIT! A larger fish comes along, feeling snacky, and it eats the small fish. Plastic and all. Does it eat just the one small fish? Of course not! Do you see the pattern being illustrated? This process of increase is called ‘bioaccumulation.’ Because of this accumulation, our Great Lakes predator fish are being found with plastic in their digestive systems [1,2].

That does not necessarily mean that humans are directly consuming microbeads. We clean our fish before we eat them. Other terrestrial predators are not as cautious. Bears, for instance, are not taking the time to clean the innards of their freshwater catch. Maybe they should, but Inland Seas does not have any volunteers prepared to walk up to a hungry bear to educate them on the pros of proper fish gutting.

Though we are not munching on microbeads with every sushi run, there is another factor to consider. Microbeads in the water have been shown to serve as carriers of toxins [2]. These toxins are digested and become part of the animal’s body, the part that we eat. There is not much, if any, documentation of serious illness in humans from consumption… yet. As microbeads and other microplastics continue to enter the water cycle this issue may prove to be more alarming.

So what was that bill again?

The “Microbead Free Waters Act” is a means to slow microbead pollution by cutting off the source. There are two sets of dates that we need to pay attention to. I will pull the language directly from the text:

In general, the amendment made by subsection (a) applies—

(A) with respect to manufacturing, beginning on July 1, 2017, and with respect to introduction or delivery for introduction into interstate commerce, beginning on July 1, 2018; and

(B) notwithstanding subparagraph (A), in the case of a rinse-off cosmetic that is a nonprescription drug, with respect to manufacturing, beginning on July 1, 2018, and with respect to the introduction or delivery for introduction into interstate commerce, beginning on July 1, 2019.

Whew. That is some serious political jargon. Let’s break it down. Part A above only refers to microbeads, not the personal care products they go into. Starting in July of 2017, the manufacture of microbeads was no longer legal. As of July of 2018, it is illegal to ship the microbeads around the United States.

The second set of dates is about the personal care products themselves. Since July 2018, companies can no longer make these products with plastic microbeads. Finally, in July of this year (2019), it is no longer legal to ship microbead personal care products throughout the United States of America.

If you go to your local pharmacy, grocery store, or salon, you can still find these products hanging out on shelves, lit up all beautifully, begging you to buy them because the act does not say anything about selling their remaining stock.

So what can we DO?!

Believe it or not, these products are better for the environment in the trash rather than floating in our freshwater seas. Look for the following ingredients in any of your soaps, shampoos, and toothpastes:

If you see any of these names in the ingredient list, toss them. If you are a chronic recycler and all around waste reduction advocate, this can be a difficult concept to grasp. But remember, these small plastic beads serve us for approximately two minutes and then spend an eternity moving through the water.

If you happen to have disposable income, buy up some of these products from stores and slam dunk ‘em into the nearest trash receptacle. The sooner these products are off of shelves, the less plastic is at risk for entering the lake!

Finally, as usual, we are a big advocate for getting loud! Check your mom’s soaps and tell her what’s up! Use your Snapchat streaks to inform your friends! Speak unabashedly to strangers who are perusing the pharmacy aisles with you! Sure, you might come off a little strange holding 12 bottles of Neutrogena and proudly saying how you are going to throw them directly in the trash, but your voice is important in this fight for plastic-free waters. If you’d like, send us your photos of microbead hauls being thrown away. Tag us on Instagram at @inland_seas_education_assoc or send us an email at isea@schoolship.org.

References

- Driedger, A.G.J., Durr, H.H., Mitchell, K., Van Cappellen, P. 2015. Plastic debris in the Laurentian Great Lakes: A review. Journal of Great Lakes Research. 41 (1), 9-19.

- Wagner, M., Scherer, C., Alvarez-Munoz, D., Brennholt, N., Bourrain, X., Buchinger, S., Fries, E., Grosbois, C., Klasmeier, J., Marti, T., Rodrigues-Mozaz, S., Urbatzka, R., Vethaak, A.D., Winther-nielsen, M., Reifferscheid, G. 2014. Microplastics in freshwater ecosystems: what we know and what we need to know. Environmental Sciences Europe. 26 (12).

This blog has been written by Rachel Ratliff, an educator for Inland Seas Education Association. Rachel obtained her degree in natural resource management with a minor in biology from Grand Valley State University. She first began her journey with ISEA as an education intern in the summer of 2018 and has a passion for experiential education as well as public outreach and communication.

Inland Seas Education Association (ISEA) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization whose mission is to inspire Great Lakes curiosity, stewardship and passion. Through hands-on, experiential learning activities, people of all ages gain an appreciation for and personal connection to our lakes, leading to a desire to care for and protect them. For more information about our Schoolship programs, data, or public sails, please visit www.schoolship.org.